You might not expect a novel about the Thirty Years’ War to be entertaining, much less funny. Those three decades of massacre, starvation, plague, and pillage littered central Europe with eight million corpses; it wasn’t until the twentieth century that the European nations once again achieved such sheer horror. And yet, despite its grim subject and despite its jacket-copy endorsement from Michael Haneke, bleakest and most depressing of bleak and depressing German directors, Daniel Kehlmann’s new novel Tyll is a rollick and a delight.

Daniel Kehlmann is a German-Austrian writer most famous for the farcical history Measuring the World; his other titles include a contemporary-set novels in stories, a ghost story, a book about an obsessed journalist, and a comic metafiction about hypnotism and hypocrisy. He’s widely read, widely translated and wildly unpredictable. His new novel has elements of earlier productions—its novel-in-story format, its lurches and meanders between humor and horror, its cast of likable fools and failed thinkers—but Kehlmann has once again written something new and different. Tyll is a magical realist historical novel, full of anachronism and absurdity, but also deeply felt.

Buy the Book

Tyll

Tyll Ulenspiegel, born a miller’s son at the turn of the seventeenth century, loses home and family when wandering Jesuit witchfinders accuse his absentminded and over-talkative father, Claus, of heresy. Over the next few decades, Tyll and various companions, ranging from an incompetent bard to a minor noble to exiled heads of state, wander a collapsing Holy Roman Empire, reaching fame but never quite managing fortune. This plot summary might make Tyll sound like a picaresque, but really the novel more resembles a pageant. Characters—most ridiculous, some pathetic, and all deluded—parade before the reader for thirty to fifty pages, then vanish. Each chapter presents its own tableau vivant of idiocy, disaster, or hypocrisy; in some panels, Tyll stands front and center, in others he capers on the fringes. The chapters proceed all out of chronological order, so that the end is the end, but the beginning is the middle and much of the beginning near the end. Anyone looking for their historical fiction to proceed in a straight line like history itself should apply elsewhere.

Historical characters appear throughout, in guises ranging from faintly silly to utterly ludicrous. The hermetic Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, here portrayed fixated magic spells, traveling with a group of scribes who take down his every word, and convinced he has deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics, perhaps gets the worst of it. Here is his scientific method:

“Kircher had grasped early on that one had to follow reason without being flustered by the quirks of reality. When one knew how an experiment had to turn out, then the experiment had to turn out like that, and when one possessed a distinct conception of things, then, when one described them, one had to satisfy this conception and not mere observation.”

Tyll Ulenspiegel resolves not to die, and if he ever did die, Kehlmann doesn’t show it. Just as the jester’s life resists endings, so too do the stories it incorporates. Crucial events, like the execution for heresy of Tyll’s father, happen offstage. Tyll’s mother is driven out of her village and out of the narrative; what happens to her after we never learn. Twice we fail to learn how Tyll escaped burial alive during a siege—the second time, Kehlmann cuts away just before his hero makes his exit. Even the narration changes. The opening chapter is narrated by a ghostly collective, the dead inhabitants of a ruined town. The next chapter flits between close third-person viewpoints, while a later chapter contrasts the actual events experienced with the version presented in a memoir a participant writes “in the early years of the eighteenth century, when he was already an old man, plagued by gout, syphilis, and the quicksilver poisoning that the treatment of the syphilis brought him.” The chaos of war, perhaps, engenders a chaos of narrative. The Treaty of Westphalia, signed in Osnabrück in 1648, ended the Thirty Years’ War. Kehlmann concludes his narrative in Osnabrück before the Treaty is written, much less signed.

I will have to trust German critics on the quality of the original publication’s writing, but I can say the English in Ross Benjamin’s translation is fluent and clever. The jesters and traveling players of Tyll sometimes declaim in rhyme and pun; as far as I can tell, Benjamin maintains the sense without losing the wordplay. If there’s something that’s lacking in this translation, it’s something that no translator can supply, namely the historical sense and knowledge that the book’s original German audience will approach the novel with.

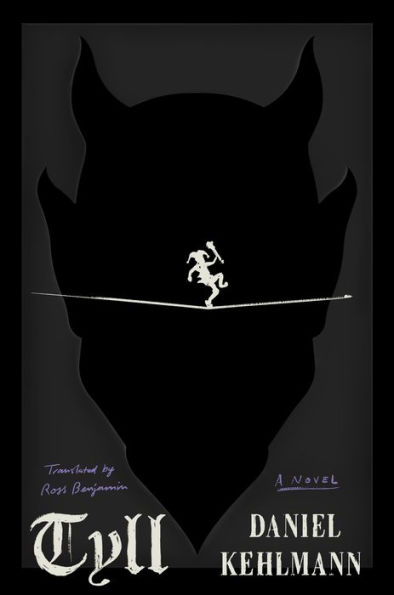

Tyll entertains his audiences with a tightrope act—he saunters, strides, roll, jumps, spins, and runs—that’s a governing image of the novel. Kehlmann himself performs a tightrope act in the book: he walks the line between the invented and the historical, the tragic and the comic, the ridiculous and the sublime. He rarely stumbles, and he dismounts with a flourish. I for one am eagerly awaiting his next performance.

Tyll is available from Pantheon.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.